A VERY BRIEF HISTORY OF WILLIAMS ARIZONA: AS IT RELATES TO THE FOUNDING OF THE TOWN, AND THE SAGINAW LUMBER COMPANY

Generally speaking, the earliest occupants of the northern area of Arizona were the peoples of pre-history, who were followed by the Hopi, Navajo and Apache tribes. The Spanish were the first Europeans to venture into this vast area, with hopes of golden cities. On one of his expeditions, the Grand Canyon was viewed by Garcia Lopez de Cardenas in 1540 (Roberts, 62.) Although awed by the vast beauty of the canyon, the Spanish were more pragmatic; they were after riches in gold and silver, not the enrichment of the soul and spirit that was inspired from such a panoramic view. The Nation of Mexico, once separated from the Spanish Crown, sent expeditions as far north as Utah.

Despite these early efforts, the high country of northern Arizona was little understood or appreciated by outsiders until the mid-1800s. It took the Mountain Men, those independent-minded trappers and wanderers of the uncharted western frontier, to venture forth and begin to chart this wilderness. These adventurers, as well as the original people who occupied and thus owned the area, had the mental capacity to map and identify key features, recall important locations, and navigate without written documents.

One such Mountain Man was old Bill Williams, who ventured into the area seeking wealth by trapping animals for the fur trade. An over-abundance of curiosity and a sense of bravado spurred him on to many adventures while exploring the area. He is well-remembered, having numerous landmarks and features bequeathed with his name. He and other Mountain Men provided invaluable knowledge for the first Anglo-American expeditions into the region.

The United States Government authorized the exploration of the western frontier by the U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers. They were tasked with providing several practical railroad surveys, and establish wagon roads to California. In 1851, Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves completed a reconnaissance of the San Francisco Mountains (North of current Flagstaff, AZ.), and the area of Bill Williams Peak (South of Williams, AZ). The subsequent report was a "snap-shot," a short documentation of the region. This further expanded the written knowledge of the area, benefiting future expeditions (Fuchs, 15: Goetzmann 244-246.)

Lieutenant Amiel Weeks Whipple assembled another expedition in July 1853 at Fort Smith, Arkansas. This expedition was tasked to explore and survey a railroad route along the 35th parallel, with special attention to the area between the Zuni villages and the Colorado River (Fuchs, 17; Goetzmann, 287-289.)

In 1857, Lieutenant Edward Fitzgerald Beale embarked on a survey and construction expedition of the wagon road that would later carry his name. Starting at Fort Smith, Arkansas, the survey and road traveled 1240 miles, to the Colorado River. One notable event was the use of camels to help transport their equipment. The road would become an artery allowing thousands of immigrants to travel to California, workers to the mines in Southern Arizona, and the movement of vast herds of sheep into the Williams area.

Passing north of Williams, the road generally followed one spring to the other, through the North Country. Years later, the North Chalender Line of the Saginaw and Manistee Railroad crossed its' path in the Spring Valley area. By the time that the railroad grade was built in 1902, the Beale Road had fallen into disuse. It is easy to imagine that the loggers had grazed their horses where camels once trod, camping on the same ground where the early explorers had slept (Fuchs, 19.)

The Bill Williams Mountain area remained relatively untraveled until the 1870s. Those who did remarked on the lush grass and tall timber growing in abundance (Fuchs, 26,27.) The 85-mile Overland Road, stretching from early Flagstaff to the Fort Whipple-Prescott area passed to the south of the mountain. In use from 1863-1882, the road was originally used by the military. From the mid-1870s until the early 1900s, large herds of sheep and cattle traversed the trail in the summer to the cool mountain meadows, grazing and fattening upon the abundant grass in the high country (Fuchs, 85.) This same road, by that time mostly abandoned, would later play an important role in the building of the Saginaw Southern Railroad.

Williams Historic Photo Project

The townsite of Williams, Arizona began as a post office (June 14, 1881) on the surveyed grade of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad (the 35th parallel survey route.) The town also served as a construction camp for the building of the railroad (Stein, VI; Fuchs 32, 34.) Ranching and the construction of the A&P Railroad played a major role in the town's early history. The town was located on the ranch of C.T. Rogers, possibly one of the first settlers in the area, having arrived in 1877.

With the building of the western section of the A&P Railroad from California, while the other half built west towards Flagstaff, the lumber and timber companies began to take an interest in the vast Ponderosa Pine forests. The first mill sites, mostly portable operations, were established in 1882, producing volumes of ties for railroad construction.

Early Williams, circa 1890. Population 200

Several merchants established stores, either on speculation of future growth or to service the existing construction camp and residents. Early photographs record a mixture of wooden structures, large tents and stone buildings. These were built along what would become Railroad Avenue, facing the expanding rail yard. Two stage lines served the region, including this up-and-coming town of Williams (Fuchs, 61.)

For a time, Williams was overshadowed by Simms- the construction camp and town located at the Johnson Canyon Tunnel site. Once the A&P had completed that project, the denizens of the town either followed the construction to Williams or drifted elsewhere.

The roadbed of the Atlantic and Pacific arrived in Williams in April 1882 (Fuchs, 56.) With the coming of the railroad came temporary freight and passenger facilities. A permanent station came in the 1900s; a freight station in August 1901 (Fuchs 116,196.) A railroad sponsored eating house was opened in 1883. Fred Harvey, a well-known provider of quality meals and service, established a welcomed presence circa 1887 (Fuchs, 98.)

With the railroad facilities, having a post office, the connecting stage lines, and a developing merchant's row, the town was developing the air of permanence. With permanence comes investment, with the hope of future prosperity. Civilization was advanced with the establishment of a school (1882). Church services were provided by circuit preachers starting in 1883. The population varied in the 1880s. The census of 1890 documented 199 persons residing in town- although this may not take into account the transient railroad laborers, saloon workers, or the outlying ranches and farms in the region (Fuchs, 58, 99,102.).

As with all frontier towns with hopes of becoming the next metropolis, wood and canvas construction brought the fear of fire. Williams would always face an imminent shortage of water to fight the fires and to slack the thirst of a growing community. It became feast or famine; the feast of fires on dry wooden structures; the famine of water to quench the devouring beast. The report on one such fire in July 1884, reveals that Williams had several mercantile, a drug store, a hotel and restaurant, and the ever-present plethora of saloons. Due to the ever-growing demand for water, the railroad began drilling wells as early as 1886. A railroad sponsored dam was built 1887 (Fuchs 70, 79,82.)

Early High School, circa 1910. Building burned down.

It must have been a remarkable edifice of learning

The Cabinet Saloon, now an Italian Bistro. Just left of the picture is a house of ill-repute.

In the Background is the Grand Canyon Hotel. Circa 1890. All three buildings still stand

The main street, known as Old Trails Highway, circa 1917.

Later it would become Route 66

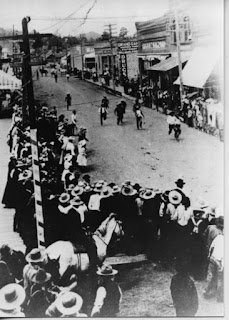

July fourth celebrations, 1909.

From 1884-1886 The A&P Railroad moved the division point to Peach Springs, AZ, causing a slump in prosperity (Peach Springs, still in existence to this day, was the source of clean water for many years for the railroad and the town of Williams.) In 1890, the town rebounded with the return of the division point. In 1901 a branch line was built to the Grand Canyon, spurring the expansion of the railroad maintenance facilities in Williams. Grazing, ranching, farming and the railroad were the underpinnings of the local economy, until the day that the lumber mill was built. (Fuchs 78, 81, 83.)

In April 1893, The Saginaw Lumber Company, of Saginaw, Michigan began building a large permanent mill, just west of the Williams township. A contingent of company employees relocated from Saginaw, Michigan. One source indicated that a large number had already arrived, with another 23 families on the way. All of the related facilities to support the mill and the employees were prudently built on the mill property (see chapter on the Williams Mill; Fuchs 109,111.)

Like most growing townships, the leading citizens (modest in number) wanted Williams to become incorporated as a city. With incorporation came the official trappings of government: a town council; a city clerk and marshal; and the contentious issue of taxation. The first attempt at incorporation took place in October 1895. By December it was nullified in court. Some surmise that the burdens of taxes and licensing fees, and some degree of meddling by the lumber company, fomented the court action to nullify the charter (Fuchs, 125.)

As earlier noted, the Saginaw Lumber Company had shrewdly built all of their facilities, including employee housing, on company property. When the town was reincorporated in 1901, all of the mill property- and related facilities- were excluded from the city limits, thus eliminating city taxation (Fuchs, 128,129.) This was possibly one of the earliest examples in the Arizona Territory of tax breaks for corporate investments.

In December 1893 an experimental telephone line was strung from Flagstaff to Williams. In 1894 a permanent line was made between the Williams Depot and the main mill. In July of 1897, a connection was made between the offices of J.M. Dennis Lumber Company in Williams, and their sawmill located 8 miles east at Walker. A long-distance line to the outside world was completed in September 1901 (Fuchs, 145,179.)

The principal industries in the early 1900s were: the livestock industry (sheep and cattle grazing): the lumber industry; and the Santa Fe Railroad. The latter built the shops necessary for a division point, further expanding operations once the Grand Canyon branch was opened.

Mining had proved unprofitable; however, there was one rich lode of pay that was left virtually untapped: tourism. As early as 1902, new hotels, eating establishments and curios shops were developed. By 1930, in addition to the railroad's Harvey House and Fray Marcos Hotel (and the old but respectable Grand Canyon Hotel,) "There were two auto camps...several mountain resorts west of town, four or five service stations, three garages...the Button and Cherokee Hotels" were open for business (Fuchs, 258.)

In 1929, the Great Depression began, eventually seeping into the daily lives of every citizen. Williams was not immune. The mill, at reduced production, continued to operate with occasional shutdowns (Fuchs 273.)

In 1933, a company commissary was established at the mill. The local newspaper was sharp and pointed in response. This became a contentious issue with the city (see Mill Post.)

In March 1941, the Saginaw and Manistee leased and then purchased the Arizona Lumber and Timber Company in Flagstaff, AZ. At the start of 1942, it was obvious that the company was leaving Williams. In June of 1942, all production was ended. In September of 1944, the city purchased the old mill site, and both dams of the Saginaw and Manistee. The new high school and housing developments now occupy the former mill site (Fuchs 263, 264.)

Williams continued on through the lean and prosperous years. Eventually the tourism industry, with the revitalization of the Grand Canyon Railway, brought stability. Today, with the promise of new recreational activities, the steady growth of the housing market, and the cult-like following of old Route 66, hope endures that this once frontier town will remain for many years to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment