THE NORTH CHALENDER LINE 1902-1904(6): HARDY HILL SPUR

COPYRIGHT; ALL RIGHTS RESERVED (5/10/22)

From 1902 until about 1904, steam engines ambled through the forests as timber was harvested along the North Chalender Line. The history of the line has been shrouded in mystery, but one thing is certain; timber was the source of profits for the Saginaw, and the Sitgreaves Mountain area grew it in abundance. The market for lumber continued to expand. The mines at Jerome and growing communities needed the lumber for buildings, and timbers to shore up new diggings. Miles of new railbed for the Atlantic and Pacific, merged into the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad (henceforth to be affectionately referred to as the Santa Fe), required carloads of new ties. Even the mill seconds, those ties rejected by the mainline railroads, were used to expand their logging cousins.

The Saginaw Lumber Company was well-placed to harvest the vast Ponderosa Pine forests, spreading over thousands of acres of land holdings that the company owned or controlled. The company had a large modern mill at Williams; logging railroad lines penetrated the woods. In the first decade of the new century, four separate logging lines owned and operated by the company were either expanding or concluding; the old Saginaw Southern; the Bellemont; the Chalender south lines; and the North Chalender. The company had to continually develop new rail lines to meet market demands and to feed the voracious appetite of the mill.

All of the lines, with the exception of the southern spur out of Williams, directly connected with the Santa Fe Railroad. The Santa Fe was a crucial component in the assembly- line operation: timber was felled, prepped and hauled by big-wheel teams to the logging spur; logs were loaded and transported by log cars to the Santa Fe connection; trainloads were hauled to the mill; timber was cut and shaped into a marketable product; then processed loads were shipped out, once again using the Santa Fe. Empty cars were returned to the logging sidings, where the process was repeated. At one time the Santa Fe began raising rates, and as a result the S&M considered building their own line to bypass the railroad (See Garland Prairie Line and the Proposed Mainline.)

The management of the S&M planned far in advance for the continued existence and profitability of the company. One piece of that plan was the development of the North Chalender Line. Before any rails were laid, many an intrigue took place before the line could be born.

INTRIGUES, LAND SALES AND GOVERNMENT LAND SWAPS

The early 1900s proved to be a crucial time period for the company. Far to the east In the Halls of Congress, plans were being made to create forest reserves with government oversight and control. Decisions made thousands of miles away began to impact the forests of Northern Arizona. The concept of sustained yield was gaining favor, coming to fruition with the Forest Reserves program. No longer would the harvest of timber be left to the whims of local control or logging interests. The Federal Government was about to make their presence known.

The Saginaw and Manistee had already acquired timber rights for thousands of acres of prime timber. Complicating further harvesting was the legacy of the Railroad Land Grants, dating from the time when the trans-continental railroads were provided Federal land. The land grants were every other Platt, resulting in checkerboard appearance on a map.

Company management devised a plan to satisfy their need for timber, and to appease the Federal Government. Why not propose a land exchange with the newly created Forest Service? They would get a continuous, homogenous Forest Reserve, and the S&M would get the same for harvesting. This would allow for the building of the North Chalender Line.

Thus ensued a flurry of negotiations and correspondence between the S&M, The Federal Government, and Doctor Perrin - owner of the vast land holdings that the other two coveted (all correspondence and records hitherto referred to are located at the Northern Arizona University Cline Library; MS NO 84, Box 13 of 15, Saginaw and Manistee Lumber Company, 4(C)2, Folder 457; 1896-1902.)

The S&M officials wanted to keep this scheme a secret. It would be advantageous to certain competitors if they found out. Officials of the company traveled wide, from Michigan to California, with particular attention to Arizona. The standard means of communication were the telegraph and the U.S. mail. Since a telegraph transmission was accessible by anyone with a telegraph office, it was decided to use coded telegrams. At stake were 86,000 acres owned by Doctor Perrin, and possibly the very future of the company.

Negotiations with the Doctor created internal intrigues within the company. Letters of the time period between officials indicated that the landowner couldn't be trusted and was causing issues. More than likely the Doctor sensed an over-eagerness by the officials to purchase his land, and he was more than likely willing to play one company official against the other. The building of the North Chalender Line was directly mentioned in the official correspondence.

In addition to negotiating with the Doctor, the company had to placate the Secretary of the Interior. Legal difficulties resulted as the government had issues with the transfer of land titles. No legal sleight of hand was being allowed. Minor disputes over the minutia of details had to be resolved, such as 1/100 and 10/100 of an acre.

Finally, in August 1902, all issues were settled, and the land sale was completed. The owner received the purchase price of $4.00 per acre ($344,000.) From September through October, the company in good faith transferred the lands to the government ledger. Thus, was created the San Francisco Mountains Forest Reserve. The railroad in return received contiguous timber rights, soon to be harvested by the North Chalender and Bellemont lines.

The company had rights to harvest the timber until January 12, 1926. This was later extended until December 31, 1950 (Box 13, Folder 458, NAU Special Collections.) On a thirty-year growth cycle, the possibility existed for a double harvest on certain timber tracts. Not a bad deal for all participants, especially the Saginaw and Manistee.

*****************

ONWARD, LAY THE RAILS!

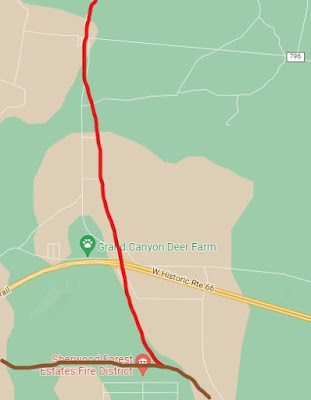

The line connected with the Santa Fe in the Chalender area, then proceeded in a northerly direction through the Pittman valley. The grade crosses the Interstate, just to the east of the overpass. The Deer Farm is just to the west.

At the now-designated Radio Hill, the grade began to encounter the foothills of Sitgreaves Mountain, who's peak soars to 9378 feet. Proceeding north-easterly, the grade passed Frenchy Hill, paralleled by FR74. Grey highlights commercial quarry area: grade is just to the south of the road near a tank. The dotted line indicates a spur that accessed the south side of the mountain.

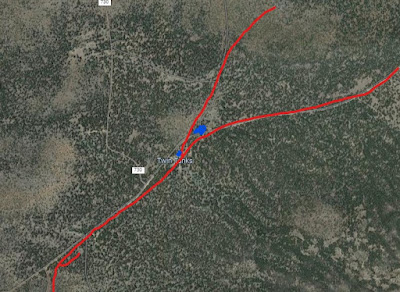

heading north-west, the grade passed to the east of Hardy Hill (highlighted in Light Blue.) The mainline parallels or is covered by FR74. Dark Blue Designates Hardy Hill Spur. Note the grade curves and follows FR141 to the East.

At Twin Tanks (marked in BLUE), one spur headed in the direction of Little Squaw Mountain.

The main line continued along FR 141

Spurs branched off of the main line, reaching deep into the timber. Several spurs were to the north of Sitgreaves mountain, near Little Squaw Mountain and Squaw Mountain. It was reported that as part of the lease the S&M was required to finish logging the two mountains. The cost of logging this area met or exceeded the profits of the cut timber, due to the ruggedness of the terrain.

Continuing on and curving to the northeast, the line passed south of Little Squaw Mountain. The line then passed near West Triangle Tank, continuing east between Section 16 Hill and R.S. Hill. Here it entered the upper Spring Valley region, with spurs radiating to B.R. Tank, Spring Valley Tank and Beale Spring (please note that large tracts of land in this area are on private property and cannot be accessed without permission.)

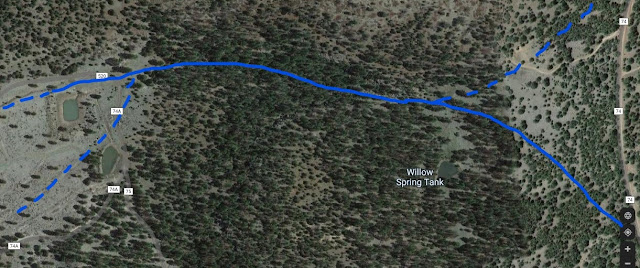

Red designates the mainline and a spur. Dotted Red, located on private property,

indicates a branch heading to the east. Light Blue is a spur heading towards

Sitgreaves Mountain. Light Tan indicates spur to W. Triangle Tank (separate posts

describe these two spurs.) The Yellow line indicates the approximate path of the Beale Road.

Another spur headed south to Sitgreaves Mountain, passing by East and West Elk Springs (W. Triangle Tank occupies the lower end of the valley.) This area was once traveled by the Beale expedition, surveying and building a road west to the Colorado River. It is possible to imagine the members of the expedition camping in the area, while camels grazed upon the lush grasslands. Certainly, migrants traveling the road west would have availed themselves of the clear, cool spring water.

The northeastern reaches of the line are somewhat blurred by the later spurs of the Bellemont line. One question has perplexed the researchers; did the two lines join deep within the forest? According to field research, the answer is yes. One branch of the N. Chalender line (1902-1904) headed east to the remote area of Beale Tank. A westerly spur of the Bellemont Line (1903-1929) made a direct approach to the same Tank, passing it and continuing onto private land (inaccessible without permission.) The two lines operated concurrently for a several years.

There are additional indications that a spur ran past Government Hole, to the area of Obsidian Tank. Another possible spur extended west from Red Tank to BR Tank. The S&M had long-term rights to harvest the timber tracts. This was a powerful motivation to continue logging the eastern reaches of the North Chalender Line. This also may have played an important part in its demise, as timber could now be hauled on the newer Bellemont line.

HARDY HILL SPUR

At Willow Spring Tank, a spur was laid, running to the west, entering a ravine just south of Hardy Hill. This spur was a unique feature of the entire line, causing much speculation by historians as to its intent. The area continues to be the focus of research for students of industrial archaeology.

The archaeological evidence shows that the spur was part of a wye near the mainline. A wye would have been used to turn the direction of a locomotive without the use of a turntable. The roadbed encountered a ravine, then opened to the west into a sandy flat area, stretching for several miles. This area provided ample room for whatever the railroad had intended.

The ravine was walled-in by basalt rock outcroppings, leaving the railroad little choice as to how to descend to the bottom. The problem was solved by building a trestle. This structure was not of an ordinary design; it was simple and functional. The trestle was formed by notched logs, stacked in square columns. The descending grade was adjusted by reducing the height of the stacked logs. Logs were then placed across the top, spanning from one structure to the next. Not a common practice for a mainline railroad, which would normally use bents fashioned from squared timbers and bolted into a bridge structure. After 117 years, the trestle still stands today, albeit showing signs of decay.

This ravine shows an abundance of Native American rock art and is one of three important sites in the region. The other two are Laws Tank (documented by the Beale expedition); and Rock Tank (located one mile north of old route 66, West of the town of Parks.) As indicated by the presence of the rock art, the Native Americans were aware of the spring in the ravine prior to the coming of the railroad. This provides a clue as to why the railroad spur was built.

After descending the trestle, the spur entered the sandy plain area. Probably one of the more interesting sites along the line, the archeological evidence indicates the company established a large logging camp. It was not unusual for the Saginaw to establish a headquarters further into the woods, as would be repeated along the then-to-be-built Garland Prairie Line. However, the Forest Service has concluded that most if not all of the structures in this area are from a later time period. This amateur archeologist proposes an overlap of the two, with the railroad initially developing the area, and the second use taking over the remaining structures after the railroad departed. You can decide for yourself, as the area is accessible. Remember that it has special protected status, as a cultural and historical site.

Some speculation is made as to what all the features mean (somewhere deep in the archives of NAU a more definitive description likely exists.) The site contains numerous foundations, a standing concrete structure, root cellars, and the remnants of large tanks (earthen water collection ponds.) Other earthen features appear to have been spurs where logging equipment may have been stored. A camp would be needed to repair the equipment, and store needed supplies. Other areas along the line could provide the space and land, yet something significant was built in this area. With all of the effort to develop it, one is led to wonder why the railroad chose to access this particular site.

WATER-such as the Native Americans had discovered in the ravine- was needed in large quantities for the thirsty loggers. Most of the camps were located near tanks or springs where horses could be watered. Locomotives needed constant refilling of their tenders, and the numerous tanks along the line could slake thirsty boilers. However, good clean, fresh water was needed for the crews and for the cookhouses. Ample supplies would be a necessity given the dry, arid climate. Men do not work long with a belly full of contaminated water. A source of clean water would help alleviate the transport of water by the Santa Fe from the Williams mill site.

A curious, yet interesting, exchange of letters began in 1903 that may shed some light on the situation (referred to documents reside in the Saginaw and Manistee collection, NAU Chandler Library, special collections.):

On January 9, 1903, Mr. M.J. Drury, Division Master Mechanic, wrote a response to Mr. G.R. Joughins, Mechanical Superintendent of the Santa Fe Railroad, Coast Lines. The letter acknowledges the repair bill, #4540-5, for damage to the Santa Fe Railroad cars 91913 and water car 30065. Notable was reference to the fact that the S&M Railroad was still using link-and-pin couplers. * Life for the rented water car on the logging railroad was hard: the sills were loose and split due to a missing bolt; a side stake pocket was broken; floorboards were damaged by fire; brake beams were broken by a derailment.

*(The Safety Appliance Act made air brakes and automatic couplers on all common carrier, interstate commerce cars, mandatory starting in 1900. The railroad could deny transport of any car not so equipped after this date. The law did not apply to logging or industrial railroads, as long as they did not interchange with a common carrier. It would be interesting to research as to when the S&M modified their equipment for the interchange with the Santa Fe.)

The Saginaw and Manistee rented additional water cars from the Santa Fe. The S&M received another Santa Fe billing on February 24, 1903 (Car Service Department Bill #77.) The logging railroad reportedly rented cars #95313, 99578 for 13 days, having been charged $15.00 during this time period. The Santa Fe had raised their rental rates from $1.00 to $1.50 per day. Also included was the billing for hauling A.T.99578 from Gallup, NM, to Chalender, 210 miles at 10 cents per mile. The total billing was $36.00.

On March 7, 1903, on company stationery, the S&M responded to Bills #77 and #139. Bill #77 was returned to the Santa Fe, the S&M insisting several errors had been made. The Santa Fe apparently had the mindset to gain as much profit from old equipment: car #95313 was an old engine tender on a flatcar, with a capacity of 2500-3000 gallons; car #99578 held 5,000 gallons. Contending to have been overcharged, the S&M argued the correct amount should be $1.00 per day. The additional charge for hauling #99578 was disputed, as no such charge had previously been made.

On March 16th WM. F. Dermont of the S&M wrote the Santa Fe, asking that the $1.00 per diem should be charged for 9,000-gallon cars, not $1.50 per diem for a 5,000-gallon car. The letter further states that the car is used on the "New branch from Chalender North and cannot get along without a water car inasmuch as the water is at one end of the line while our camps are at the other." He further contended that they should not be charged for Sundays, when the car was not in use.

What can be surmised is that the S&M had a daily need for large amounts of fresh water. Apparently, water was available but had to be hauled a great distance to the camps. Renting cars of dubious heritage from the Santa Fe, then being charged for repairs, was causing a strain on profits. Later in company history, the S&M apparently purchased their own water cars.

The water issue could be mitigated if an on-line source of clean water could be exploited. The Hardy Hill spur just might have been the answer to the problem.

This is a fascinating area, often studied by student and scholar alike. However, it is a historically significant site that is legally protected. Due prudence and respect should be shown for its historical nature. Access to the remote area can be difficult, and only the experienced hiker should access the site.

Much speculation can be made by the author; however, deference should be given to more scholarly research. Somewhere within the vast archives lies the untold history. Hopefully, this will encourage the publishing of additional information, possibly unlocking the mystery that shrouds Willow Springs.

RECREATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES

Be aware a large portion of the north Chalender Line is on private land. Respect private property. During inclement weather, the roads can be difficult. Use due caution; high clearance 4X4 is recommended. Consult an up-to-date map and plan your trip in advance.

The area that the rails once passed can be accessed by several roads. This area is best explored from the main confines of well-marked forest roads. At Parks, stop by the general store at the intersection of FR141 and old Route 66. Then head north on FR141, also known as Spring Valley Road. Be respectful of the posted speed limits, particularly at the school just north of the intersection with old Route 66. This road will take you to the Spring Valley area and passes Government Prairie. This prairie is a nature area, a little slice of natural history and a good place to hike, if you enjoy wildflowers and beautiful scenery in the spring. Access is limited; consult your map or the folks at the general store.

As you head north, look for the trail markers with the camel sign. This is where the Beale Road crossed the landscape. For further information on the Beale expedition check with the Visitor Center in Williams and read the chapter in this book.

At Spring Valley, you can continue north on FR144 until it intersects with Highway 180. If you turn left onto FR141, this will take you through the area just north of Sitgreaves Mountain. At the intersection of FR141 and FR74, going straight will take you to Highway 64. Turning left on FR74 (Compressor Station) will return you to Interstate 40, having passed through Pittman Valley. Enjoy the drive, bring a good map and look for the areas mentioned in this section, and be safe.

No comments:

Post a Comment