THE SAGINAW SOUTHERN RAILROAD 1898-1909

(All maps courtesy of Google Maps.)

Appears to be 2 Truck Shay #556, and #212 Shay. Both working the line in Barney Flats area, circa 1900. This would be on the original Saginaw Southern. Courtesy National Archives, neg. 48-RST-4C-2

From 1866 to the early 1900s, railroad fever had spread across the nation. Several transcontinental railroads were either being built or were in the process of incorporating. The vast frontier attracted farmers seeking fertile ground, ranchers wanting open range to run cattle and sheep, and business interests seeking to develop the vast mineral wealth of the west. These opportunities captured the imagination of more than one corporate boardroom.

A north-south rail line in Arizona would connect the Atlantic and Pacific and Southern Pacific Railroads. This would expedite the transportation of goods within the state, and open new markets to the outside world.

In 1883, one such route was attempted from Flagstaff, Arizona. Proposed in 1881, the Arizona Mineral Belt Railroad would build south to Globe, Arizona (Schupper 23, 24.) Work began midsummer of 1883 on a tunnel to pierce the Mogollon Rim. By September, the money had run out. Additional funding was provided, but by 1887 the project was $30,000 in debt (Schupper 29,30.) On December 4, 1888, the remaining assets were sold at auction. Renamed the Central Arizona Railroad in 1889, the financial panic of 1893 brought this plan to an end (Stein 7.)

The Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railroad (SFP&P) was chartered on May 27, 1891. This would connect Ash Fork to Prescott, Arizona, and eventually reach Phoenix. Construction began on August 17, 1892, from the Atlantic and Pacific at Ash Fork, Arizona. This was quickly completed, allowing transportation by rail.

The new Williams mill needed timber, and the company looked south to the vast timber holdings waiting to be harvested. The Saginaw Southern Railroad was incorporated as a common carrier railroad on September 22, 1898. This would shorten the haul of products from the high-country mills to the burgeoning markets of Prescott and Jerome. Whether this can be considered an overreach by a logging company with aspirations to becoming a major player on the railroad map, is a subject for debate. At a minimum, if the line failed as connecting route, it would still allow access to the vast timber holdings. Whatever the outcome of such debates, it proved to be a bold move by a conservative group of investors.

As a common carrier, the Saginaw Southern was allowed to condemn private property for the right of way. Any disputes had to be resolved in court (Stein 31.) The wagon haulage of logs to the mill would be replaced by the railroad. The new railroad had aspirations of reaching Jerome, and possibly Prescott, AZ. (Fuchs 144.) One early map, dated July 23, 1918, showed a proposed route south from Williams connecting with Perkinsville, along the Verde River (map with letter, July 23, 1918, NAU Cline Library special collections.)**

The Saginaw Lumber Company decided to proceed south from Williams with all speed. Work began in earnest during the fall of 1898. By June 30, 1899, three locomotives were running over 6 miles of track. Just past the Barney Flats Area, the railroad grade encountered obstacles not unknown to experienced construction crews (These were men who had learned their trade in the Michigan forests.) Canyons, hills, and marshy meadows were given their due consideration, then were overcome by tried-and-true methods.

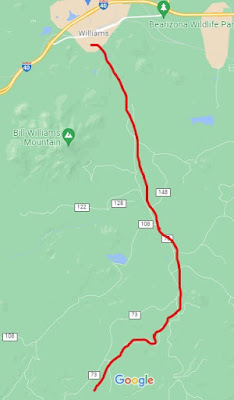

The route of the Saginaw Southern. The original grade generally follows

Perkinsville Road, until diverging on FR 354. The grade ends abruptly

at the edge of the pine forests

The grade intersected the old Overland Road, an 85-mile wagon road stretching from Flagstaff to the Fort Whipple-Prescott area. In use from 1863-1882, it was used by the military and civilians to travel to and from the nearby settlements. Vast herds of sheep were moved along the road from the valley to the summer grazing areas in the high country. At one time there were three separate seasonal migration trails leading into the high country. An old-time forester once said that records indicated some 175,000 sheep passed by in one year on just one trail. The road was less traveled when the grading crews came to the area.

The old Overland Road would have been known to the surveyors, and to think that they used part of the trail by coincidence would be unlikely. The old road provided access from Summit Tank, through a narrow canyon, descending a steep southerly grade of about 3%, and to the northeast of Davenport Knoll. The line would then curve to the northwest of the Knoll (now private property), reaching Davenport Tank. From there, the line headed in a southerly direction, trying to make the best of the difficult terrain until abruptly ending somewhere south. The Saginaw Southern had been outdone by a poor survey, and the relatively easy route of the already built SFP&P.

Overland Road, Davenport Tank Area.

RED designates the route of the Saginaw Southern.

BLUE is Davenport Knoll.

ORANGE indicates the steep grades and canyon area.

Forest Road as it heads south to the canyon. Historical Sign

Davenport area.

One question remains; why didn't the railroad continue on to the far-flung horizon, namely Jerome? Later reports, circa 1921, stated that the railroad had chosen the worst of surveys, causing a financial strain (Stein, 31,91.) The area for many square miles is studded with steep hills and rock-strewn gulches. Geared locomotives, such as Shays then in operation, would have had little trouble traversing the steep canyon grade. Shays have remarkable traction, but they are also slow in operation. The canyon is a seasonable dry wash; the monsoon season's torrential rains would devour the roadbed at will. Efficient and safe operations would be jeopardized by the challenges of a difficult survey.

Rumors of extensions occurred in 1901 and 1909 (Fuchs 144.) The railroad would have to justify the cost of expansion by providing some other source of revenue, besides logging. Laying rail through the Verde Canyon, to the productive mines of Jerome might be the answer. This hope was soon dashed, as the Verde Valley Railroad built through the Verde Canyon to Clarkdale in 1911-1912 (Wahmann, 21.) This effectively cut off any hopes of any further southward expansion. One can imagine that the company retreated to higher ground, where quality timber stands could be harvested.

Further south on the remnants of the line, the quality of timber became dubious. Old cut logs still exist, revealing knotty snags, not worthy of hauling to the mill. South of this point, the proposed grade entered the juniper forest zone, sparsely dotted with small mines.

With all hopes of expansion having been quashed, the operation reverted to the everyday mundane task of a logging railroad. It is also possible that people (including the newspapers) continued to refer to the old line by its former name, long after the legal identity had ended. The length of the line fluctuated, until in 1904 when the line was first reported abandoned (Glover; Stein, 31.) The rail bed reached no further south than section 29-T20N, R2E. This would be in the area of Deadman Wash and May Tank. (Stein 31.)

It is possible that the corporate identity of the Saginaw Southern ended in 1904 or 1909. To abandon the status as a common carrier at an earlier date would cause problems for any chance of future expansion. The Williams News proudly proclaimed in their banner that the Saginaw Southern was an entity well into 1912. Local residents would have referred to the southern line by its original name, just as they referred to the mill as the "Saginaw" for many years to come.

If the Saginaw Southern was revived as a common carrier entity, then the company could once again exercise condemnation rights on private lands. In1921, they attempted to revive the rights with the Arizona Corporation Commission, at a time when an all-Saginaw East-West mainline was being proposed (Stein, 37.)

Additional information, supported by archaeological evidence, indicates that a robust and active presence of the logging railroad existed beyond 1904. It was reported that 3 locomotives of the Saginaw Southern were working south of Williams in 1908 (Fuchs 181.)

.....

The Saginaw and Manistee Lumber and Timber Company was active over a vast area to the south of Williams, with timber rights generally spreading west of Perkinsville Road; southeast to the Tule and Saginaw tanks; south from Williams to Pine Flat Tank near FR105; North of Bear Canyon, and West of Sunflower Flats. According to S. Sales Kaibab, South End Unit, 7/30/35 (NAU Map 522), There are indications on the maps that some sections were harvested prior to 1907.

Later timber sales occurred along Pine Flat Road, to JD Dam, as far as Bear Canyon in 1935-1937. Further research indicates in this specific area and time period mechanized harvesting and trucks ruled the roads.

.......

A document has been uncovered: A congressional Bill that would allow the Saginaw Southern to proceed south to Jerome crossing the Forest Reserve. This would acknowledge that the railroad had initially surveyed to Jerome (55th Congress, 3rd Session; House of Representatives Report #1674 ((H.R. 11061)) December 14, 1898.) This document was viewed on eBay, appearing to have been torn out of a Congressional Ledger. The author does not purchase documents that have a suspicious pedigree or provenance.

Further, the author has viewed a document in the N.A.U. archives for what appears to be a work order/ request for quote on a narrow-gauge Shay. This is further evidence that the Saginaw was seriously considering a line to Jerome, or a connect with its narrow-gauge railroad.